Stasi Stumped, Reputations Restored

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

Forty years ago in Cold War Germany, the Stasi set up some United States Air Force officers and ruined their careers. While they were not court-martialed, the effect on their lives was dreadful; they steadfastly maintained their innocence to no avail. For those of you who have no idea what the Stasi was, it was the East German outfit that generated the classic “spy-versus-spy” stereotype of men in trench coats who marked postal boxes with one half of a chalk “X” on rainy nights.

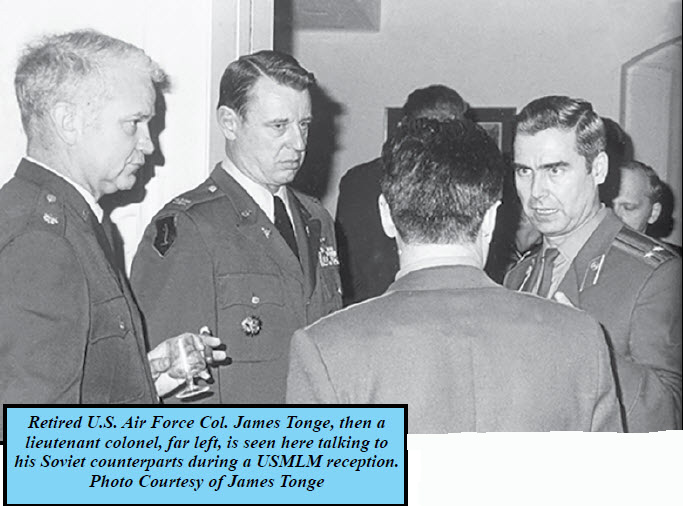

In 1979, two USAF officers were part of an American group called the U.S. Military Liaison Mission. In a word, their job was to “build” relationships with their German Democratic Republic (GDR) counterparts in order to keep an eye on them, and the Stasi did the same. They would have meals together, celebrate holidays together, and it was the wane of the glory days of what is portrayed so skillfully in Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies.

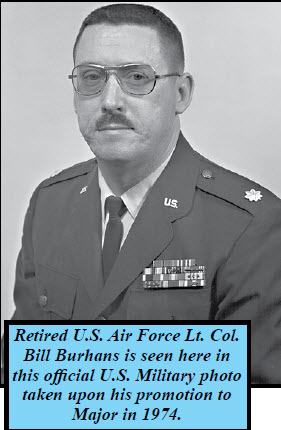

One of the men, Lt. Col Bill Burhans, was the designated driver on the night of December 29, 1979, bringing home fellow US officers as well as Soviet counterparts from a holiday party. Strangely, he lost control of the car and it ran into a bus. A fellow USAF Lt Col. James Tonge, told Bill to move the car over to the shoulder. Burhans sat there frozen, and Tonge said he looked like he had been “hit in the head with an ax at the slaughterhouse.” Burhans’ response was not consistent with the accident, and he claimed he had been drugged. Burhans had his blood tested; bromazepam showed up, which has the ability to cause drowsiness, lack of coordination, memory loss, and dizziness.

In a memoir that Burhans wrote for his children, he said, “To my knowledge, there was no standard operating procedure in place” to respond to being drugged. “In my case, no one bothered to do any investigation other than to implement the [U.S. Command Berlin’s] directions” to pursue it as a drunken-driving case,” he noted. While Burhans was not court-martialed, he did take a non-judicial punishment, and essentially his career was over. The greater tragedy was that Burhans actually did develop substance and mental health problems that for decades nearly destroyed him.

Tonge’s blood work had traces of a heart medication that he wasn’t taking, and he testified that they both had been “slipped a mickey.” The problem was, no one believed them except for one USAF officer who had no power to help. Now, 40 years later, it turns out that it’s true, Burhans and Tonge had been “dosed,” and the proof of the plot comes from old Stasi files that have recently been unearthed and exposed.

There is a happy end to this story. Both men, who are in their 80s, have been completely cleared of any alleged wrongdoing, and while they didn’t get to have the careers for which they dreamed, now they can face any and all naysayers with confidence. “For me, the most unusual part of the story is finding written evidence that the Soviets drugged us,” said Tonge, now 85 and living in Charleston, S.C. “It would have been good to have had that information when Berlin authorities were treating it as an ‘alcohol-related incident.’”

In retrospect, Burhans said, despite the professional and personal price he paid following the incident, “I take it as a compliment that the Soviets considered me that much of a threat.”

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner