Publisher’s Point: The Dutch Girl

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

Audrey Hepburn is one of those actresses about whom it has always been easy to say, “They just don’t make ‘em like that anymore.” She made her film debut in 1953, the year I was born, and won an Oscar for Best Actress for her performance in Roman Holiday opposite Gregory Peck. She was the epitome of gamine grace, and rarely have I seen someone better able to communicate without saying a word.

Audrey was genuinely feminine, and not in a contrived manner. She was soft-spoken, demure, graceful, and gracious. Her beauty within and without was rare, and the sound of her voice was like water. Her eyes were pools of softness and mischief, and she had a captivating sense of humor. She is considered by the American Film Institute to be the third greatest actress in film history, behind Katherine Hepburn and Bette Davis.

When it came to fashion, Audrey is still considered a timeless icon, and while stunning in everything from ribbed turtlenecks to custom designed gowns by legendary designer Edith Head, one of the things that made her so jaw-droppingly exquisite was her modesty. Let’s just say that Audrey would have never claimed a “wardrobe malfunction” at the Super Bowl, because nothing she wore could have ever gone that wrong.

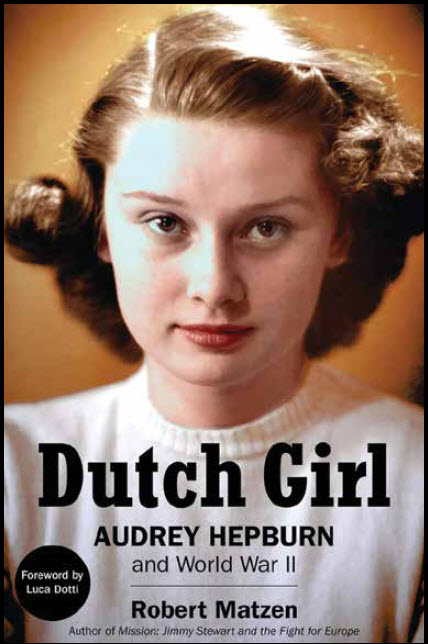

All of the above about Audrey Hepburn is relatively well known by fans of classic films, but I would like to commend to you a story of rare betrayal and remarkable re-invention that is the crown jewel of her life. It’s called Dutch Girl, and tells a story of courage under fire that is not roared, it is whispered. Audrey Hepburn was born of Dutch nobility, and for openers, she had “daddy hunger” that seems to have never been satisfied. Her mother and father started out as fans of Hitler and Mussolini, and considered themselves to be ardent Fascists. Her father left his family, her mother went to meet Hitler in Germany in 1935 and waxed nearly worshipful in his presence. Because her mother knew that England was going to be attacked by Hitler in the Blitz, they returned to Holland because that seemed like a safe move. It was there in Holland, however, that once Hitler invaded the Netherlands, Audrey’s mother began to see his true colors and eventually turned away from being a sycophant.

For her part, Audrey became involved in the Dutch Resistance. This lithe ballerina used to put messages for downed pilots and other resistance members in her ballerina-style flats and go for walks to deliver them. One day she came out of the woods only to find that Nazi soldiers were approaching. She kept her wits about her, popped down, picked meadow flowers, flashed that intoxicating grin, handed them to her enemies, and walked away. The pilot was never discovered.

Audrey was also an accomplished dancer, and here’s where it gets really good. The Nazis, of course, were all about control, over all aspects of life, and that included the arts. You could not perform without their approval, so Audrey would perform for nobility in a mansion in the interior of Holland, and the money raised went to the underground. They would put curtains in all of the windows so Audrey’s performance remained hidden. Talk about a charity gala… In an audition film/screen test when she was asked about it, with sweet impishness she giggled and said, “Oh, they didn’t know about it.”

In the spring of 1944, Audrey nearly starved to death because the Nazis were trying to starve the Dutch. She survived by eating tulip bulbs, but was never again strong enough to pursue the rigors of dance full time. Instead, she built an epic acting career, and spent the last part of it working with UNESCO while rescuing starving kids. To watch her interact with them was achingly tender. Cancer took her in 1993, and I have no doubt she faced that the way she faced everything, with a highly tempered, resilient grace. Read the book—you’ll find uncommon triumph over trauma.