Publisher’s Point: Being A Being Worth Dying For

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

By: Ali Elizabeth Turner

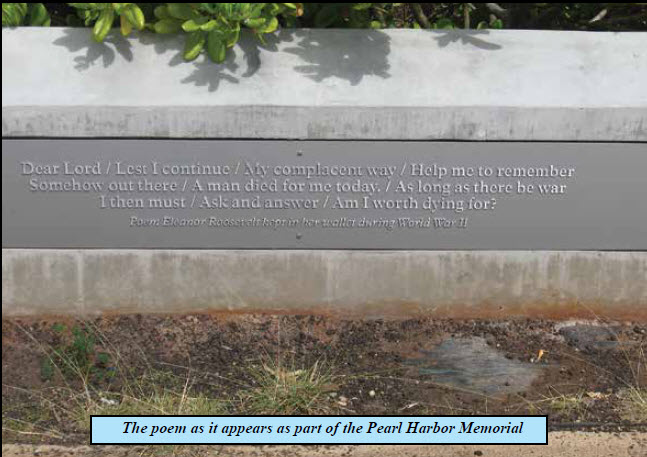

During WWII, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt published a poem that appears to have been untitled, but is generally referred to as “Eleanor Roosevelt’s Wartime Poem.” She kept it in her wallet, and would take it out from time throughout the course of the war and read it. It goes like this:

Dear Lord,

Lest I continue

My complacent way,

Help me to remember that somewhere,

Somehow out there

A man died for me today.

As long as there be war,

I then must

Ask and answer

Am I worth dying for?

I had never known about this poem, and the way it came to me was quite by accident. I had been at a BNI meeting this past Tuesday morning, which is held every week at the Vets’ Museum. I was back in the office near the copy machine and happened to glance up, only to discover it up on the wall close to the staff door. It had been hanging there for years, I had walked by it many times, and then, boom! There it was. I took a moment to look it over, and was stopped in my tracks. Tears came to my eyes when I reached the part that said, “Am I worth dying for?”

As a believer who gave my life to Christ 50 years ago this year, I have wrestled many times with that question from a spiritual perspective, and am no stranger to the battle to align my sense of worth and identity to what the book of Ephesians says about me: that I am forgiven, quickened, called, sealed, chosen, redeemed, adopted, gathered, accepted in the beloved, His workmanship; in a word, saved. One day I will be saved to the uttermost, and there will be no experiential gap between how I want to act and how I do act.

But oddly, Calvary isn’t what brought tears to my eyes. Even though a sinless Man, the Son of God died the most hideous death in history for me, and did so for reasons that are above my pay grade, somehow that isn’t what was getting to me. It was being reminded that it was a soldier, many soldiers, no doubt, that have died for me from the beginning of our country until now. And it is because of the belief that the American Experiment was worth defending at any cost, and that life, even my life, is worth dying for that I can be deeply touched by the words of a woman with whom I would have disagreed largely had I been alive during WWII.

The whole experience caused me to “ask and answer” what I and you could do to be worth dying for, and I came up with one word: “Accountable.” If we can develop the habit of owning all of our actions, the good, the bad, and the ugly, we will become the people that are worthy of our soldiers shedding their blood for our natural freedom. They won’t have to do it based on internalized principle, they will know that we are worthy. Let’s be.