Modern Slavery

By: Mae Lewis

January has been deemed Human Trafficking Awareness Month, so this column space is going to be dedicated to just that. Human trafficking is a broad topic. It essentially means the trade of humans for anything from sex slavery to the sale of human organs and tissues. But the broad definition of this term should not lessen the horror of what it truly is — the commercial exploitation of human beings.

According to the International Labor Organization (an agency of the UN), forced labor alone (which is only one component of trafficking) was a $150 billion industry in 2014. Trafficking was discussed very little in mainstream culture in 2014, but the industry is growing by leaps and bounds. Human trafficking is the second largest crime industry in the world, just behind drug dealing. According to a 2020 report, over 25 million people worldwide are in slavery. For context, this is equal to the population of the continent of Australia.

Traffickers prey on vulnerable populations; homeless youth are particularly vulnerable due to their lack of community, their naïveté, and lack of access to services. A lack of access to critical services or basic unmet needs is the number one cause of exploitation. People without food, a place to sleep, income, or a feeling of stability will be the first to be preyed upon.

It is estimated that more than 1/5 of the homeless youth population in America has been trafficked. To bring that into focus, there are over 2 million homeless youth every year. That means over 400,000 children are trafficked every year in the United States. In the state of Alabama alone, 6000 victims pass through the state daily.

But trafficking isn’t as straightforward as children being smuggled up and down the I-20. To compound the issue, rural areas have the problem of “familial trafficking”- which is essentially when a parent or guardian is allowing their dependent or child to be trafficked. Many parents are given no option but to allow their children to be trafficked, in their home, through threats of bodily harm or other horrific scare tactics. This cultural “norm” is just as much a problem in the rural United States as it is in faraway places like Cambodia or Thailand.

The reality is that the horrors of trafficking are not something that happen in other places, they are happening here and now, on our soil. A sobering fact is that in 2021, the human trafficking trade will gain further inroads into the American culture. The implications of the pandemic and the destabilization of our government will mean that the number of people who are vulnerable to exploitation will increase.

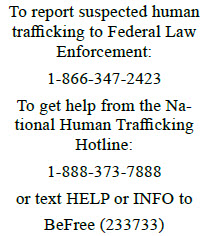

What can be done? We must demand that prosecution for traffickers be increased, and also expand our effort to identify and care for victims of trafficking. Writing to our government leaders is an actionable step that anyone can take. Additionally, it is important to recognize the signs of trafficking and how to help someone who is a victim.

Here are the indicators of human trafficking as given by the Department of Homeland Security (“Not all indicators listed are present in every human trafficking situation, and the presence or absence of any of the indicators is not necessarily proof of human trafficking”):

* Does the person appear disconnected from family, friends, community organizations, or houses of worship?

* Has a child stopped attending school?

* Has the person had a sudden or dramatic change in behavior?

* Is a juvenile engaged in commercial sex acts?

* Is the person disoriented or confused, or showing signs of mental or physical abuse?

* Does the person have bruises in various stages of healing?

* Is the person fearful, timid, or submissive?

* Does the person show signs of having been denied food, water, sleep, or medical care?

* Is the person often in the company of someone to whom he or she defers? Or someone who seems to be in control of the situation, e.g., where they go or who they talk to?

* Does the person appear to be coached on what to say?

* Is the person living in unsuitable conditions?

* Does the person lack personal possessions and appear not to have a stable living situation?

* Does the person have freedom of movement? Can the person freely leave where they live? Are there unreasonable security measures?

By: Mae Lewis