COVID-19 And The Military

By: Sandra Thompson

By: Sandra Thompson

I have been asked several times since the pandemic started, “How are veterans holding up during this time?” I half-jokingly answer that we will be fine! As veterans, we are accustomed to being told when to go, when to stay, and of course, to “do more with less.” This is not the military’s first encounter with a pandemic. As the reality of the coronavirus epidemic confronts the nation, with the looming possibility retired military medical personnel may be recalled for duty, it brings to mind the national efforts during the flu pandemic in 1918. The Spanish influenza, as it was labeled, was the greatest, most lethal disease the world has ever known.

A commonality between the Spanish flu’s H1N1 and the COVID-19 coronavirus is that both are considered “novel,” which is to say, they are so new nobody in either era had any immunity to them. There were no vaccines for the Spanish flu and there are currently no vaccines for COVID-19. One reason the Spanish flu was so lethal was there were no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections; so control efforts around the globe were limited to non-pharmaceutical responses like isolation, quarantine, disinfectants, and limiting public gatherings, although then as now, they were applied erratically. In this time of the COVID-19 pandemic, you can’t go long without hearing mention of “social distancing” and “flattening the curve.”

While those terms might sound like some modern scientific theory that government officials and scientists have just come up with, you may be surprised to learn that these methods to stop the rapid spread of illness are due to hard lessons learned during the Spanish flu pandemic, which swept the globe almost exactly 100 years ago.

The public health authorities implemented fundamental measures to control the epidemic that dated back to medieval times of the bubonic plague. To reduce the transmission of the pathogen, measures were taken to prevent contact. Public health orders were framed in an understanding of the scientific theories of how the influenza microbe spread through the air by coughing and sneezing, and their conception of the pathogenesis of influenza. Since they concluded that the pathogen was transmitted through the air, efforts to control contagion were organized to prevent those infected from sharing the same air as the uninfected. Public gatherings and the coming together of people in close quarters were seen as potential opportunities for the transmission of the disease.

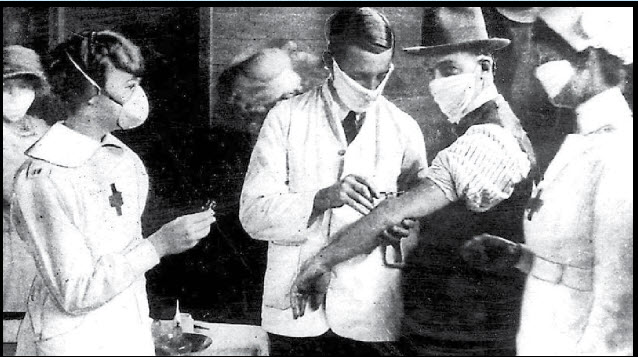

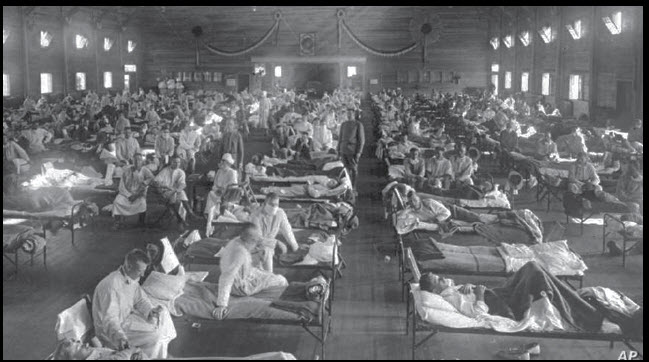

The epidemic challenged the military healthcare team to care for huge numbers of wounded soldiers during World War I, and somehow not be overwhelmed by patients infected with the hypervirulent strain of influenza. When patients became dramatically ill from a hemorrhagic pneumonitis that rapidly progressed to acute respiratory distress syndrome and death, what did the nurses do to care for the vast numbers of people? In this pre-antibiotic era, good nursing practices rather than medical therapeutics were the most important interventions for patients to recover from the influenza. Nurses worked tirelessly and diligently to provide the care and preventative measures needed to fight the disease. Since there were only palliatives measures for the flu and the pneumonia, isolation practices, asepsis rules, and strict routines were the priority standards of care.

It appears history is repeating as the nation struggles to find a cure for COVID-19, we continue to employ the age-old measures of isolation, quarantine, disinfectants, and limiting public gatherings. Unlike the Spanish flu epidemic, today’s military medical personnel, active-duty, reserve, guard, or retired all stand ready to answer the call to provide the best care possible and assist in researching the development of a vaccine to end the current crisis.

By: Sandra Thompson

Director, Alabama Veterans’ Museum