By: Yvonne Dempsey

By: Yvonne Dempsey

The year is coming to an end, and what a year it’s been! However, signs of the holiday season are everywhere bringing hope to us all as we celebrate the birth of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, our light in the darkness and our help in despair.

Aside from the decorated trees, glitter and tinsel, and bright lights, the sound of Christmas carols fill the air. Most people have a favorite carol, while others don’t care for them much. Whether it is a spirited, fun song or a gentle, beautiful song, these holiday tunes invoke feelings of joy, nostalgia, sadness, loneliness — a myriad of emotions.

Because of COVID-19, the holidays during this year have been different from many past holidays for most of us. During this Christmas season, we may be spending more time alone instead of with family and friends. However, we must not forget that those serving in our military who have to been spend holidays away from their loved ones. One of the things many veterans can remember from Christmases spent away from home is that one carol that they heard or sang that was a link to home and Christmases past.

During the Civil War, the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote the poem, “Christmas Bells.” In a depression after losing his wife to a house fire in 1861, the widowed father of six was further saddened when his oldest son, who had run away from home to join the army, was wounded in battle and sent home to recuperate. Longfellow was miserable listening to the Christmas bells chiming. Instead of ringing in peace on earth and goodwill among men, he only saw hatred and felt deep despair. But as the bells continued to ring, he was reminded that God is not dead or asleep and that there was still hope for personal and national peace. His poem originally included two verses directly referencing the Civil War, but when the poem was set to music several years later, becoming “I Heard The Bells On Christmas Day,” those verses were omitted from the carol making it timeless song of hope.

World War I saw horrific bloodshed with over 25 million killed or wounded; but in the midst of this horror, a Christmas truce was called between the warring factions along the Western Front. The impromptu truce reportedly began with the sound of Christmas carols being sung in the silent night. Behind a row of Christmas trees that the Germans had decorated with candles, German officer and tenor with the Berlin Opera, Walter Kirchhoff, sang “Silent Night,” first in German and then in English. This was followed by carols sung from both sides; finally, all joined in singing in Latin, “Adeste Fideles,” “Oh Come All Ye Faithful.” The enemies climbed out of the trenches, shook hands, exchanged small gifts of cigarettes, food, buttons, and hats. They enjoyed playing a brisk game of football on Christmas Day. Although the truce was short-lived, it was a brief moment in history when peace, sharing, and joy emanated from the singing of a Christmas carol.

One of the first Christmas carols popularized during World War II was “White Christmas.” Written by Irving Berlin, a Jewish Russian immigrant, it became one of the most important wartime songs due to the timing of its release and the type of emotion that the song evoked. Seventeen days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Bing Crosby made the first live radio performance of the new song, which makes no reference to war but is just a personal reflection about Christmas and one’s longing for it. The nostalgic and introspective lyrics struck a chord that exemplified the national mood at the time. The desire to be home for Christmas was a feeling that was amplified by the war. Millions were entering military service and were spending Christmas away from home for the first time.

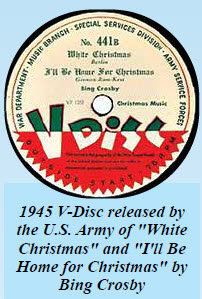

Another emotional Christmas song from WWII, “I’ll Be Home For Christmas,” has become the most requested song at Christmas USO shows. The song is sung from the point of view of a soldier stationed overseas writing a letter to his family. He tells the family he will be coming home and to prepare the holiday for him, and he requests snow, mistletoe, and presents. The song ends on a melancholy note, with the soldier saying, “I’ll be home for Christmas, if only in my dreams.” Music executives felt that that line was too sad for what should be a joyous time of year. But instead of making soldiers overseas sad, it filled them with hope. Even if they could not share Christmas at home with their loved ones, their memories of Christmases past and hopes for future Christmases at home would carry them through. Bing Crosby recorded the song with “White Christmas” on the flip side. The record was released as U.S. Army V-Disc No. 441-B and U.S. Navy V-Disc No. 221B. Although the song was popular with Americans overseas and at home, in the United Kingdom, the BBC banned the song from broadcast because they felt the lyrics might lower morale among British troops. Nevertheless, the song was still heard and loved by many British soldiers. The song remained at the top of the charts for weeks and earned Cosby his fifth gold record. Because of this record, the GI magazine Yank said that Crosby “accomplished more for military morale than anyone else of that era.”

During this Christmas season, despite the turmoil and struggles of this past year, may we all find our moments of peace and joy in even the smallest of things. May we remember our military, especially those serving in places far from home, and military families; veterans, especially those suffering physically and mentally; and all first responders and medical personnel.

The staff and volunteers of the Alabama Veterans Museum wish you all a safe, joyous Christmas season. In the words of the song, remember — “God is not dead, nor doth He sleep.” Our fervent hope for all is “peace on earth, good will to men.”

By: Yvonne Dempsey